Necular Stress Test and Blood Pressure Reading

- Published:

Practice stress testing every bit the significant clinical modality for management of hypertension

Hypertension Research book 35,pages 706–707 (2012)Cite this article

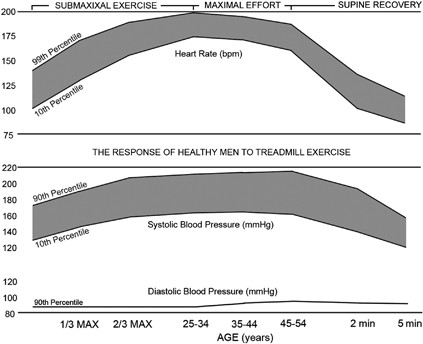

The response of blood pressure during exercise stress testing is an important evaluation parameter when such testing is used equally a clinical diagnostic modality. Several studies have associated the blood pressure level response with the severity of hypertension or the likelihood of undiagnosed hypertension in patients, who are at risk for essential hypertension.1 Nevertheless, exercise stress testing using a treadmill is unremarkably used to diagnose and/or assess the effects of handling for coronary avenue disease. Twelve-atomic number 82 electrocardiography, heart charge per unit and claret pressure responses and exercise tolerance are typical measures for evaluating exercise stress testing. The criteria for clinically meaning electrocardiographic changes, for example, ST segment changes, have been defined and are routinely practical in the clinical direction of coronary artery disease. Heart rate responses including chronotropic incompetence divers by Ellestad2 have been established. Normal values for middle charge per unit responses to exercise are known equally 'the predicted maximal center rate by age'. Heart charge per unit and blood pressure responses are ofttimes used as parameters for predicting myocardial oxygen consumption as not-invasive indices; the heart rate and double product are calculated by heart rate multiplied by blood pressure during exercise stress testing. The normal ranges of claret pressure response to exercise stress testing are as shown in Figure 1.three Normal systolic and diastolic responses to practise stress testing should not exceed 220 and 100 mm Hg, respectively. Systolic blood pressure level of >230 mm Hg is generally considered hazardous. According to the recommended guidelines for do stress testing, elevations in either systolic and/or diastolic blood force per unit area to 250 and 130 mm Hg, respectively, are indications to terminate the test.

Normal physiological responses to submaximal and maximal exercise treadmill testing derived from apparently healthy men anile 24–54 years old (adopted from Wolthuis et al. 3).

Lima et al. 4 reported in this issue of Hypertension Research that age and body mass index (BMI) are pregnant predictors for an exaggerated blood pressure response (EBPR) during do stress testing. An EBPR is defined as an increment in delta systolic blood pressure of⩾7.v mm Hg/METS (metabolic equivalents) and/or systolic blood pressure at the peak of the practise exceeding 220 mm Hg or a delta diastolic blood pressure level increment of ⩾15 mm Hg compared with resting values. They also studied associations betwixt EBPR and insertion/deletion polymorphisms of angiotensin-converting enzyme and M235T of angiotensinogen. However, they found no significant relationships. Others have found that the exercise-induced hypertension expressed as EBPR by Lima et al. 4 correlates with subsequent cardiac eventsv in patients with cardiovascular diseases. In improver, a hypertensive blood pressure response to exercise in healthy individuals can predict the development of hypertension.6 These results suggest that changes in blood pressure during exercise are associated with the pathophysiology of hypertension. Thus, the findings of Lima et al., in which clinical parameters such equally age and BMI are significantly indicated for predicting EBPR, are notable and useful for interpreting results of routine exercise stress tests.

Age and BMI are both associated with sympathetic activity and peripheral vascular resistance during exercise stress testing. Reports indicate that the main machinery for practice-induced hypertension or EBPR is a failure to reduce peripheral vascular resistance during do.six Vasodilator capacity is impaired in the skeletal muscle of hypertensive patients during exercise.vii Many other factors that regulate peripheral vascular tone during exercise accept also been reported. Among them, sympathetic tone is nearly important for determining peripheral vascular resistance.8 Aging might increase peripheral vascular tone during exercise through increasing sympathetic activity.8 In addition, aging itself could increase peripheral vascular tone through impairing endothelial role that is also a reported determinant of exercise tolerance in humans.nine An increased BMI is a sign of obesity and the combination of obesity, mild hypertension, glucose intolerance and dyslipidemia is the typical clinical presentation of metabolic syndrome. Sympathetic tone is generally more activated in individuals with, than without, metabolic syndrome. Thus, the findings of Lima et al. 4 in which age and BMI are significantly associated with exercise-induced hypertension or EBPR are logical and rational. Table ane shows that the cumulative increment in mean systolic claret pressure amid older adult men is larger in response to a piece of work load expressed as a METS increase (piece of work load progress).10

Practice stress testing is mostly considered as a typical tool for diagnosing coronary artery affliction or determining practise capacity. Exercise stress testing is ofttimes practical during exercise rehabilitation programs for patients with cardiovascular disorders. If the clinical significant of practise-induced hypertension or EBPR could be understood in more than item, exercise stress testing could be used as a clinical tool for evaluating hypertensive patients and/or individuals at high risk of developing further hypertension in the near future. Furthermore, exercise stress testing might exist used for evaluating the effects of anti-hypertensive therapies. Prospective clinical studies should be performed, such as follow-upwards of hypertensive patients and salubrious individuals with EBPR, to determine the significance of EBPR for predicting the development of organ harm or untoward outcomes. From this attribute, the recent report by Lima et al. 4 published in the Journal of 'Hypertension Research' is very valuable.

In contrast, a pregnant relationship between EBPR and insertion/deletion polymorphisms of angiotensin-converting enzyme or M235T of angiotensinogen has non been identified. As these polymorphisms are established as significant factors in the pathogenesis of hypertension, the role of polymorphisms in EBPR should be further investigated in the virtually futurity.

References

-

Allison TG, Cordeiro MA, Miller TD, Daida H, Squires RW, Gau GT . Prognostic significance of exercise-induced systemic hypertension in healthy subjects. Am J Cardiol 1999; 83: 371–375.

-

Ellestad MH, Wan MK . Predictive implications of stress testing. Follow-up of 2700 subjects after maximum treadmill stress testing. Apportionment 1975; 51: 363–369.

-

Wolthuis RA, Froelicher VF, Fischer J, Triebwasser JH . The response of healthy men to treadmill practice. Circulation 1977; 55: 153–157.

-

de Lima SG, de Albuquerque MFPM, de Oliveira JRM, Ayrers CFJ, da Cunha JEG, de Oliveira DF, de Lemos RR, de Souza MBR, east Silva OB . Exaggerated blood pressure response during exercise treadmill testing: functional and hemodynamic features, and take chances factors. Hypertens Res 2012; 35: 733–738.

-

Miyai Due north, Arita M, Miyashita Thou, Morioka I, Shiraishi T, Nishio I . Blood pressure response to centre rate during exercise exam and risk of future hypertension. Hypertension 2002; 39: 761–766.

-

Palatini P . Exaggerated claret force per unit area response to exercise: pathophysiologic mechanisms and clinical relevance. J Sports Med Phys Fitness 1998; 38: 1–9.

-

Bail V, Franks BD, Tearney RJ, Wood B, Melendez MA, Johnson L, Iyriboz Y, Bassett DR . Exercise blood pressure response and skeletal musculus vasodilator chapters in normotensives with positive and negative family history of hypertension. J Hypertens 1994; 12: 285–290.

-

Hashimoto I, Miyamura M, Saito K . Initiation of increment in muscle sympathetic nerve activity delay during maximal voluntary contraction. Acta Physiol Scand 1998; 164: 293–297.

-

Takase B, Uehata A, Fujioka T, Kondo T, Nishioka T, Isojima Grand, Satomura 1000, Ohsuzu F, Kurita A . Endothelial dysfunction and decreased exercise tolerance in interferon-blastoff therapy in chronic hepatitis C: relation between exercise hyperemia and endothelial role. Clin Cardiol 2001; 24: 286–290.

-

Fox SM, Naughton JP . Physical activity and the prevention of coronary heart disease. Prev Med 1972; 1: 92–120.

Author information

Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ideals declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this commodity

Cite this article

Takase, B. Exercise stress testing equally the significant clinical modality for direction of hypertension. Hypertens Res 35, 706–707 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/60 minutes.2012.47

-

Published:

-

Consequence Date:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/60 minutes.2012.47

hickersonainal1980.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.nature.com/articles/hr201247

0 Response to "Necular Stress Test and Blood Pressure Reading"

Post a Comment